Author: Mitchell Kiefer

PhD student in Sociology

During our Consuming Nature workshop, we discussed at various times the shift that the Anthropocene represents in our thinking. My own project is an analysis of the changing narratives within natural history museums, understanding the focus on ideas such as the Anthropocene as not only scientific statements about the world, but political and cultural arrangements. The emergent popularity of the Anthropocene – epitomized, perhaps, by its inclusion in a major institution such as Carnegie – suggests a particular understanding of the relationship between nature and culture. Just as ‘modernity’ may best be understood as a collective mindset of advancement rather than a realist description of social processes, the Anthropocene may be best understood as a collective understanding of nature-culture, reflective of unique and contingent social forces. What, though, are the social conditions that are reflected in this idea? This is too large a question to answer in a blog post. Instead of trying, I’ll suggest a few insights from specific examples of the Anthropocene in natural history museums.

A crisis consciousness? If people only act in times of crisis, and the impacts of climate change are slow onset, the Anthropocene may represent a way of matching scale. By situating the pace of climate change in geologic eras, the changes look quite rapid, indeed, and may become more easily perceived as a looming crisis.

Natural history museums such as Carnegie are institutions that wield cultural authority, and shape the ways people understand the natural world. Along with a new narrative of the Anthropocene, museums are also adopting new roles. One scientist with an administrative role at Carnegie told me the museum is now outward looking, drawing inspiration from the public and current social issues in shaping displays, exhibits, and programs. This represents a more general trend that speaks to the development of Anthropocene narratives. People in charge of these institutions recognize a relationship between people and science that may be new to major natural history museums. Another scientist with a similar administrative role suggested that Carnegie is acknowledging its role in delivering scientific information to the public in the context of people losing faith in and questioning science.

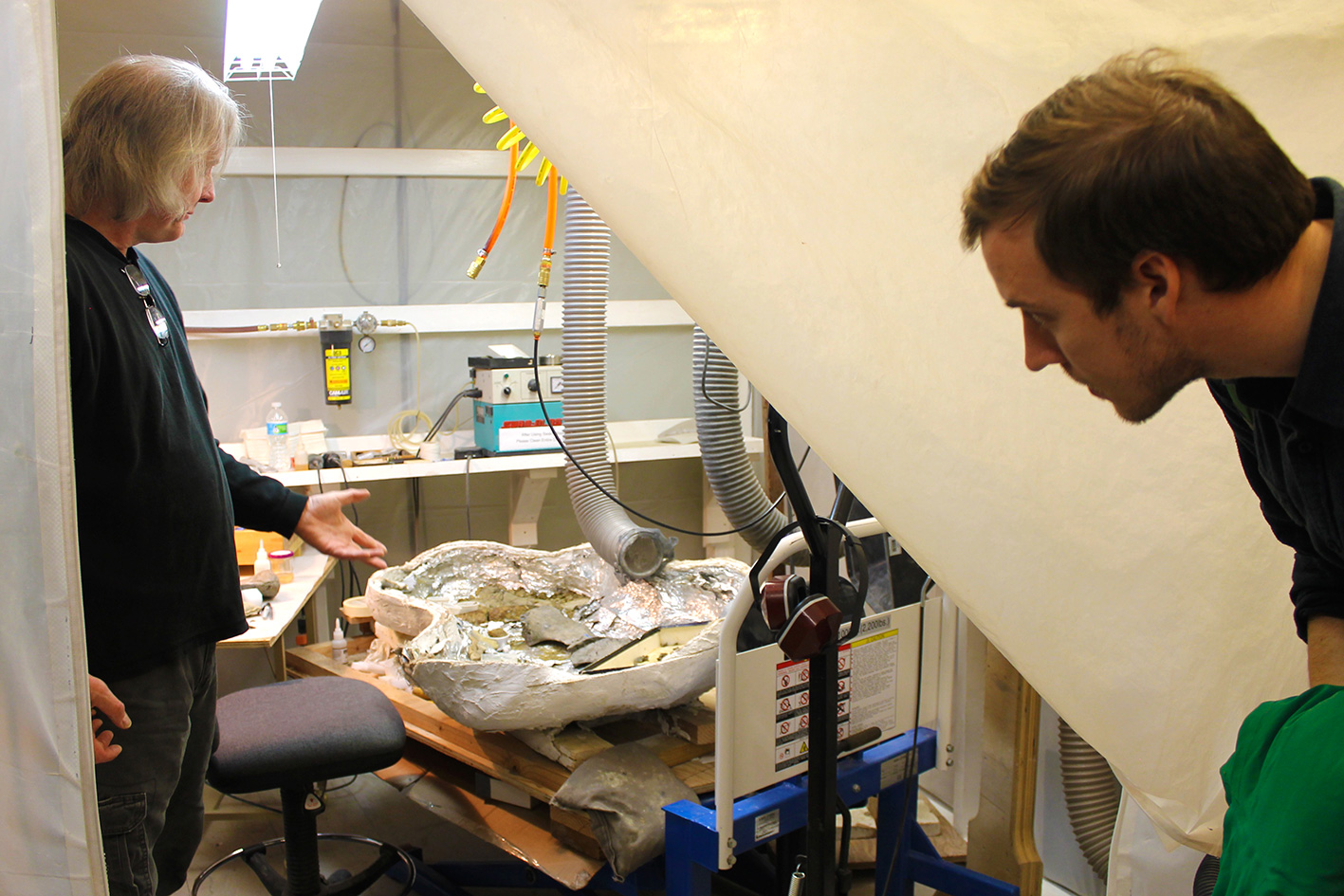

To reconnect science and people, Carnegie is becoming more reflexive in how it displays and communicates information. The work of human scientists is proudly displayed, as is the work in constructing dioramas. More information is given on the processes of producing exhibits, and displays are incorporating more interaction between nature out there and people.

What does this mean for communicating the Anthropocene and the possibility of a crisis consciousness? The new ways of displaying and the new content in displays does something different than suggest a new geologic era imposed by humans (though this, too, is suggested). What the Carnegie museum is doing is more reflective of the Anthropocene as a new way of understanding the relationship between nature and culture. Carnegie shows that yes, in fact, people have relationships with nature in ways that influence each other. Whether this change in narrative was born by some internal realization within scientific disciplines, a need for struggling museums to find funding, some other reason, or a combination of dynamics is a bigger question to be asked.

I do want to suggest, though, that a narrative that re-connects people and nature, as well as people and science, seems to reflect the scientific community’s perceived need for people to 1) acknowledge the possibility and extent of human-induced ecological, geological, and biological changes, and 2) interpret that as crisis. This is carried out in museums like Carnegie given the realization that museums can be more than holders of artifacts and drivers of scientific inquiry. They can direct public understandings, both scientific and cultural.

Learn more about the Collecting Knowledge Pittsburgh initiative here