Patricia Smith. November 7, 2017

Conservation is often an essential part of museum and gallery work that is often overlooked by the casual visitor. As an intern with Gretchen Anderson, head of the Section of Conservation at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, I developed a range of skills in conservation that have been relevant for the preparation of Narratives of the Nationality Rooms: Immigration and Identity in Pittsburgh. Our Museum Studies Exhibition Seminar had its own conservation tasks to complete, which included creating condition reports for the items generously loaned by the Nationality Rooms Office and University Library System (ULS) archives. Condition reports can take many forms, depending on the type of object and the goal of the report. For our purposes, these reports serve as an intake record to document any damages that may occur in the various stages of transport and exhibition. The Documentation team was in charge of completing these reports. The following images detail some aspects of the objects that a conservator in a museum or a gallery might be asked to address.

One of our key loans is a bronze rooster. This sculpture exhibits some physical damage, particularly around the base (Fig. 1). Notice the warping and bending. The physical damage does not necessarily devalue the object; damage and markings are part of its history and can reveal information such as provenance and production.

In addition to physical damage in this case, there is also chemical damage. The green patina on this bronze sculpture of a Benin Queen Mother is a classic example of a chemical process called oxidation (Fig. 2). Bronze is an alloy that is primarily made of copper, and copper is a metal that is highly susceptible to oxidization. This means it reacts with oxygen molecules in the environment to form various copper oxides, which are usually harmless to the object and sometimes even desired because of the color. These oxides then continue to react to combine with elements such as sulfur and carbon. The Statue of Liberty, for example, is actually covered in an oxidized copper patina. It was once a warm brown. However, if the copper begins to combine with chlorides present in the environment, it will form copper chlorides, which can lead to a dangerous form of deterioration called “bronze disease.” At some point after our exhibition concludes, the Benin Bronze Queen Mother should be checked to ensure that the oxidation process at work here is not causing damage to the sculpture itself.

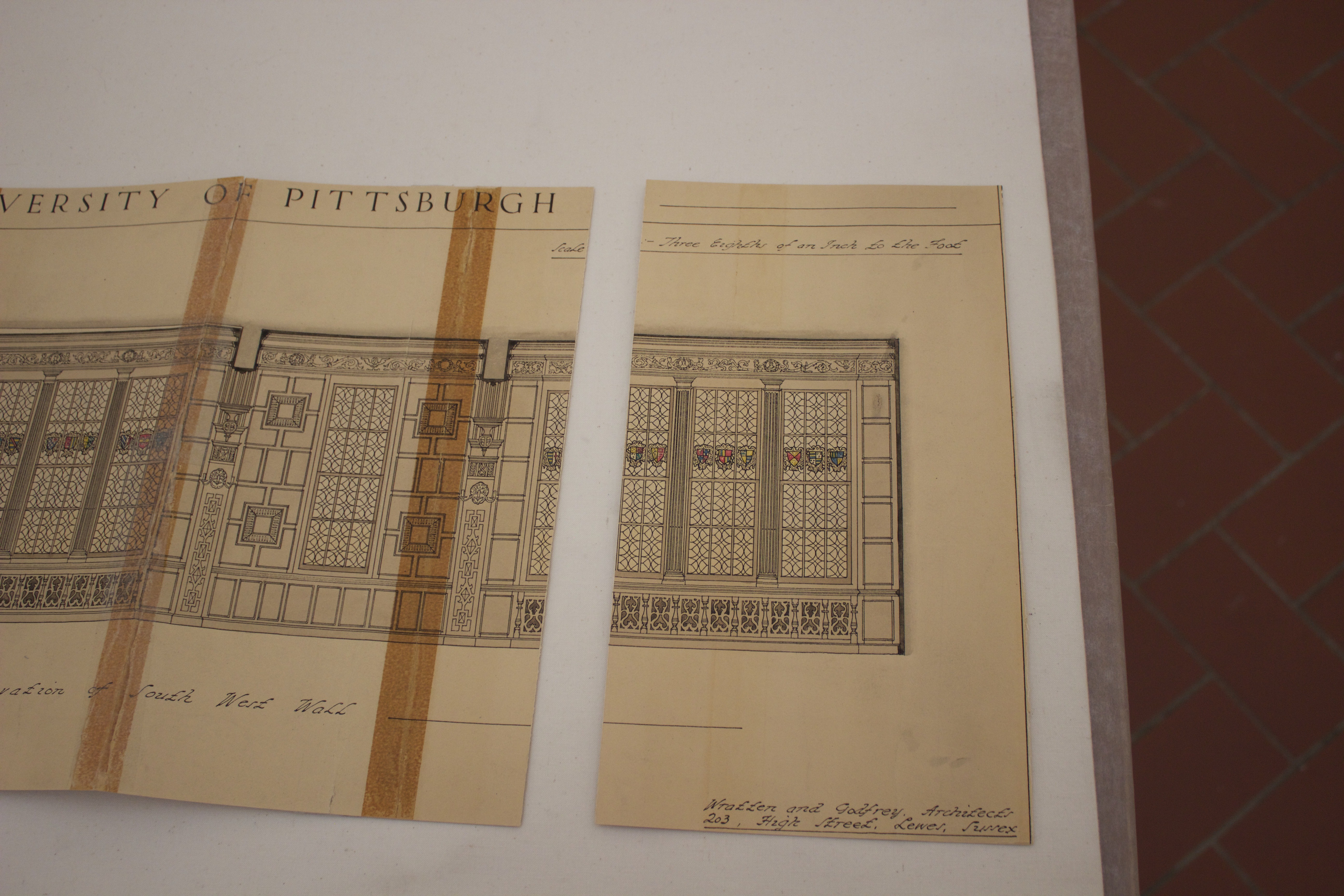

Besides three-dimensional objects, conservators also work with paper objects like books and archival documents. The Archives & Special Collections Center of Hillman Library loaned several fragile documents for our exhibition, including an architectural design for the English Room (Fig. 3). Like the Benin Bronze discussed above, many of these documents display signs of physical damage. In the case of the English Room drawings, we took photographs to show that the creasing and tearing evident here is old damage, and did not occur during the course of our exhibition.