Author: Brittney Knotts, PhD student in Critical and Cultural Studies in the Department of English and Making Advances Workshop participant

Let me start by saying, I study children’s culture—but, I am not interested in the culture that adults assume children use or in the culture that we often attempt to thrust upon them. Rather, I am interested in what children do to shape and create culture. I am interested in how they write, converse, play, and work, as well as how they subvert a lot of the ideas handed to them by adults. Perhaps not surprisingly, the voices of actual children aren’t always the loudest in the archive. But, of course they aren’t—and this is what I expected. While parents may momentarily hold on to the art or writing of their children, or we may covet out our own childhood diaries and notes, what place do these voices occupy in archives that house important historical documents and rare texts?

Because of this, when I took part in the University of Pittsburgh’s “Making Advances: Sex, Gender and the Politics of Images” workshop this summer I was ready to look at sex education guides from the 20th century, specifically those made for girls. I was not disappointed; Pitt’s University Library Systems have a great collection of sex and etiquette guidebooks and the Heinz History Center holds a fascinating record of the first implementation of sexual education in Pittsburgh public schools. I had all but given up on finding the voice of a child in a Pittsburgh archive.

Enter the amazing archivists at the Senator John Heinz History Center. I seriously can’t say enough good things about the archives and archivists at the Thomas & Katherine Detre Library & Archives. First, the archives hold about anything you could think of related to Pittsburgh’s history. Second, the archivists are amazingly attentive. I started this workshop interested in sex education materials. Not only did the archivists have boxes pulled, but they also pulled a single box about a young Pittsburgh girl that they thought might be interesting. Since I am specifically interested in girlhood, the staff thought the memory books of a teenage girl would be of interest. And they were.

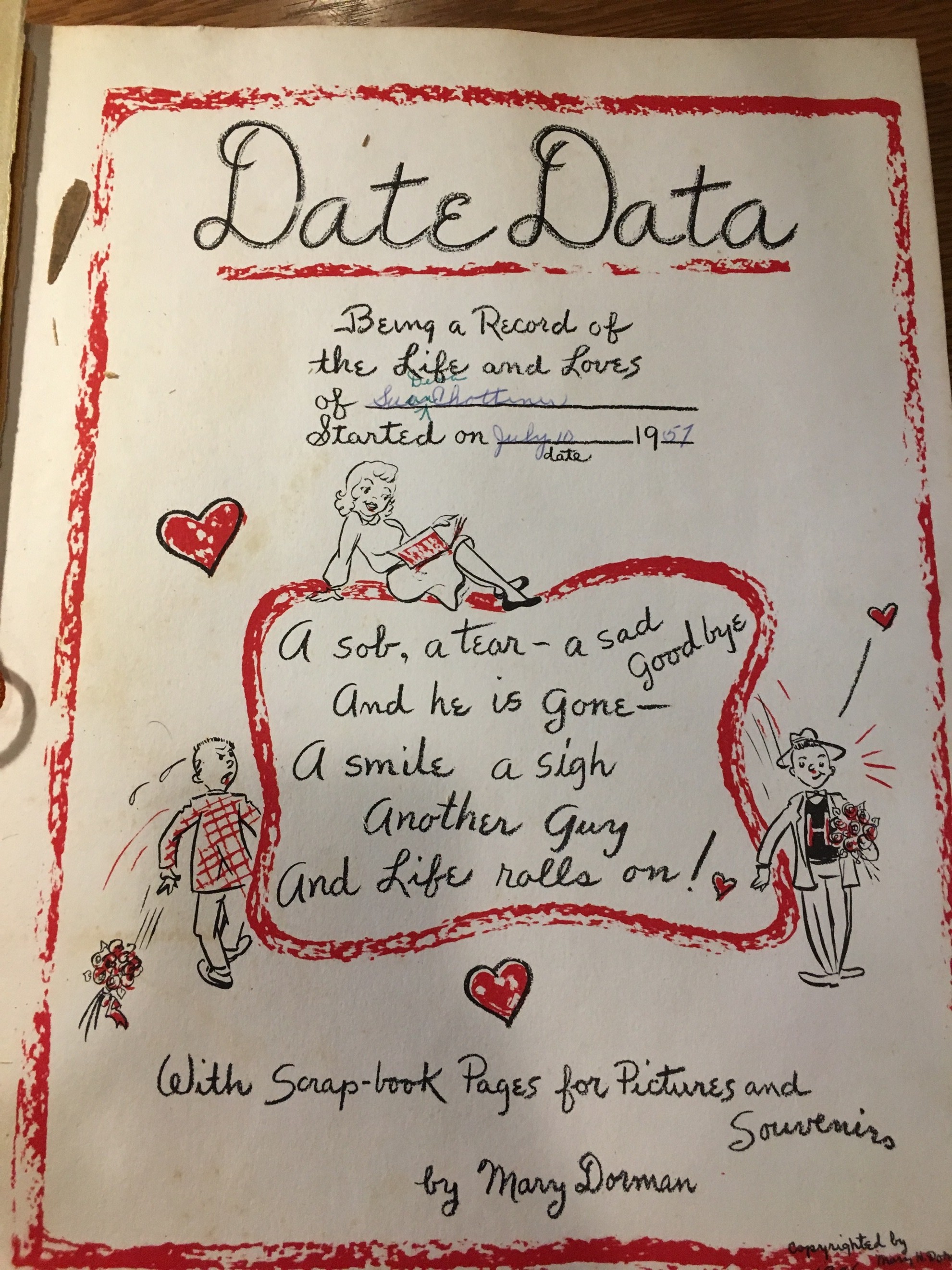

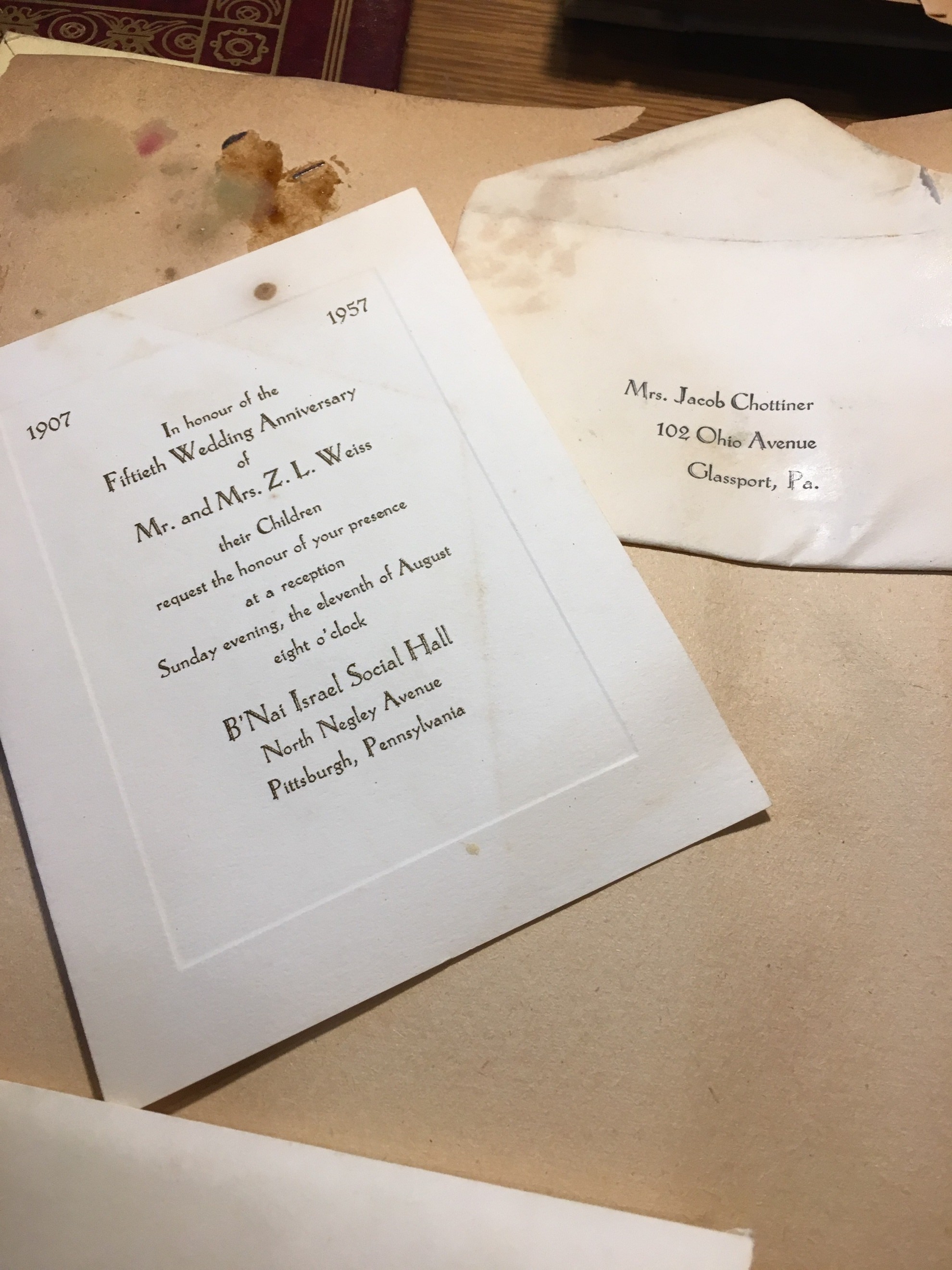

The box was a donation by the Weiss family of albums and family memorabilia. Buried under a family album and a book of family trees, I found Sue Chottiner’s book of “date data” and (what appears to be) a briefly kept memory book spanning from 1956-1957. Sue appears to be a teenage girl at the time that she kept these notebooks. There is something special about holding someone’s past in your hands. The pages, which were never meant to be preserved for half a century, have begun to crumble and the folded papers taped or glued therein have started to fall out. This is how children can exist and be preserved in archives.

The date book appears to be a mass-produced book with both blank pages and date review templates to fill out. The book provided Sue with prompts such as “This is where we met,” “Off-the-cuff comments,” and “Places where we’ve gone.” My favorite response to “off-the-cuff comments” was her assessment of her senior prom date, Jimmy, as “a great kid and good dancer.” Along with these blank writing spaces, there are check boxes offered to assess her date’s personality as well as “how he rates when it comes to dates.” For Jimmy, Sue checked off personality boxes for “jazzy dresser,” “good time Charlie,” and “big brain.” However, she did not rate him. It appears that Sue only used this book twice to keep data on her dating life.

While her dating data book offers a snapshot of Sue’s dating life, her memory book gave an overview of a complex and social girl. Sue attended Emma Kaufmann Camp in 1953 (and potentially other years). From the camp she preserved a marriage certificate to Jimmy (yes, the same Jimmy from senior prom it appears), addresses of several friends, and a song book. She was active in the Jewish community, often keeping bulletins, song books, and memorabilia from her friends’ Bar Mitzvahs. She also documented her school life with schedules, notes from teachers, and awards and certificates she earned. Sue commemorated her life thoughtfully and with purpose. She took her work seriously, equal to any writer that we consider worthy of study.

While I find these artifacts fascinating, piecing together Sue’s life is difficult. Her organization is counterintuitive to me, and I find her handwriting difficult to read at times (I imagine Sue would say the same about my organizational methods and handwriting). But I must remind myself that this writing isn’t for me. It was never meant to be. As Carolyn Steedman reminds us in her work on children’s story writing, we must “look for what the writing does for the writer, not what the writer does to it, nor what it does for us” (99). This is worth keeping in mind when thinking about the scrapbooks of Sue. She seems to have used these memory books for documenting her own life, for not only keeping track of her favorite moments but also for making a claim that she, in fact, was here.

Now I wonder what other children may be whispering in archives, waiting for someone to discover their histories, their lives, their memories. Perhaps I may start to reconsider my own research objectives and the places my research may lead. Most importantly, the child must be at the forefront, and I must give them the space to speak.

References

Steedman, Carolyn. The Tidy House: Little Girls Writing. Virago Press, 1987.

Learn more about the Making Advances Workshop here